⚡️Hello, and welcome

This domain used to belong to the brilliant engineer working to bring Tesla's legendary turbine power generation technology to the People, Jeremiah Ferwerda. Please support him by signing up for his patreon here: Jeremiah's Patreon.

You can also find his work and live demonstrations of working Tesla turbine he's proto-typed on his youtube channel. Jeremiah's YouTube.

- You can find his current website here: Myteslapower.com

This is a fan maintained website, whose only purpose is to help drive attention and support to Jeremiah and his team in progressing this incredible project. With the support contributed, the project has been promised to be open-sourced and Jeremiah appears to be 100% commited to seeing this through. There are many mentions of deals being offerred to the project, however Jeremiah's turned them all down as their interests do not align with his goal. Deals that would potentially take the project private, or worse, shelved by companies with no interest in open-sourcing this technology and it's extremly encouraging to see Jeremiah openly mentioning turning such offers down.

Details on my understanding of Jeremiah's Tesla Turbine

To fan boy out a little, want to summarize many key pieces of information related to this project that took me a while to understanding after watching most all publicly available content on Jeremiah's work. (And other behind the scenes members of his team of course.)

Mechanics of Ferwerda's Tesla Turbine Designs

Ferwerda's advancements often feature multi-stage configurations and specialized operating modes, such as cryophorus mode for cold steam testing. In this setup, the turbine sits between a hot tank (evaporating water into steam) and a cold tank (condensing it), all under vacuum. The temperature differential creates a pressure gradient, driving steam flow through the turbine without external pumps. For instance, in a 6-inch diameter prototype, the hot tank reaches 180–200°F while the cold tank starts at 57–60°F, building a 120°F differential. Vacuum levels are adjusted (e.g., -1 PSI below ambient), and materials like copper in the cold tank enhance condensation and heat transfer. This results in high rotational speeds—over 42,000 RPM without load, with peripheral speeds exceeding Mach 1 (supersonic)—while minimizing vibrations and noise through bearing refinements.

In his two-stage supersonic prototypes (e.g., with 28mm rotors), the first stage uses centripetal flow (inward spiraling) to propel the second stage's centrifugal flow (outward). The first stage can hit 234,145 RPM, while the second reaches 90,217 RPM. A critical mechanic is the "fluid gearbox" concept, requiring at least a 3:1 disk surface area ratio between stages (e.g., 2 disks in stage 1, 6 in stage 2) for optimal viscous coupling and vacuum creation. Without this, back pressure builds (up to 30 PSI at high RPMs), causing resonance, potential rotor-casing contact, and inefficiencies. When optimized, the second stage generates enough vacuum to self-sustain using atmospheric pressure alone, creating a symbiotic amplification where stages boost each other. Telemetry tools track RPM, and tests show dramatic pressure drops (50–100% performance boost by reducing exhaust to ~1 PSI from 15 PSI).

These mechanics position Ferwerda's turbine as a potential replacement for less efficient engines, with applications in renewable power via low-grade heat sources. His work continues through prototypes, videos, and community-funded refinements, aiming for practical, scalable energy production.

The Tesla Turbine: Basics and Mechanics

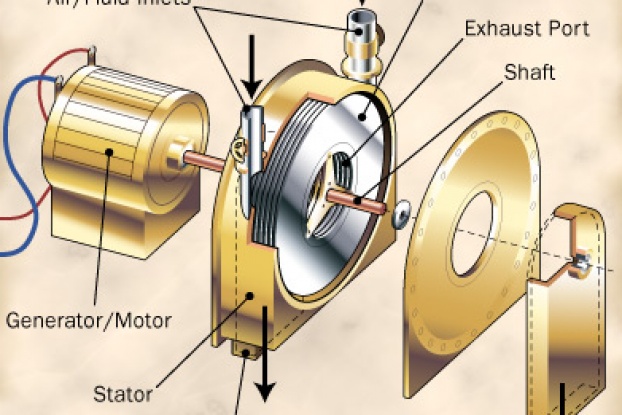

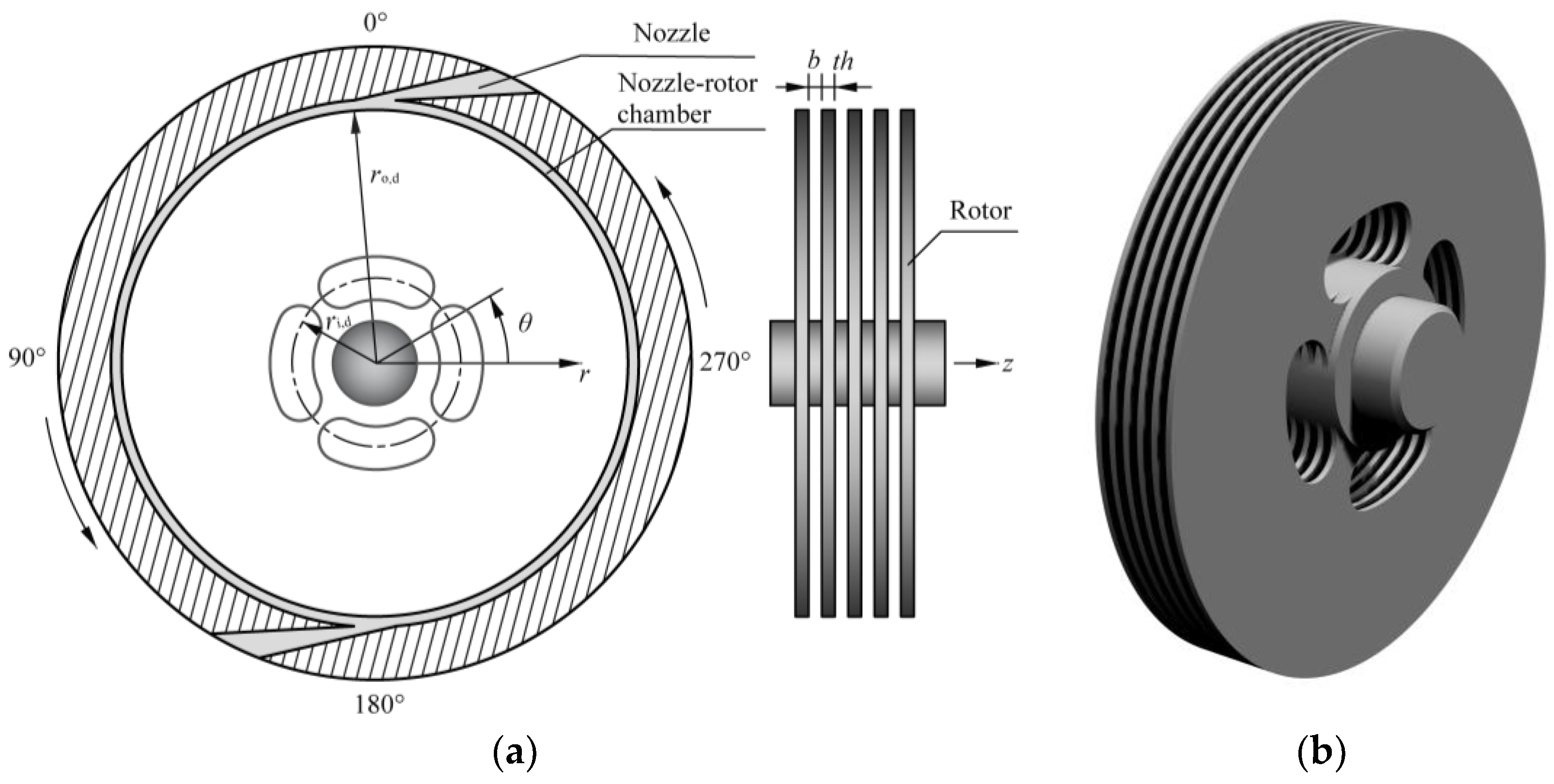

The Tesla Turbine, patented by Nikola Tesla in 1913 (U.S. Patent 1,061,206), is a unique bladeless turbine that harnesses fluid dynamics differently from traditional designs. At its core, it consists of a series of thin, parallel disks (typically made of metal or composite materials) mounted on a central shaft within a cylindrical casing. The disks are spaced closely apart—often between 0.4 mm and 1 mm—to optimize performance.

Key Mechanics:

- Fluid Entry and Flow Path: High-pressure fluid (e.g., steam, air, water, or gases) enters tangentially through nozzles at the outer edge of the casing. This creates a spiral, inward-flowing path toward the center of the disks. The fluid moves radially inward while rotating, following a helical trajectory between the disks.

- Energy Transfer: As the fluid flows, it "sticks" to the disks in a thin boundary layer (typically a few micrometers thick). Viscous drag and adhesion transfer the fluid's kinetic energy to the disks, causing the rotor assembly to spin. The fluid's velocity decreases as it moves inward, converting its momentum into rotational torque on the shaft.

- Exhaust: Spent fluid exits through ports near the center of the disks, often under reduced pressure. In some designs, this creates a partial vacuum that enhances efficiency.

- Efficiency Factors: Theoretical efficiency can reach 95% under ideal conditions, but practical values range from 20-60% depending on fluid type, disk spacing, RPM, and inlet pressure. It performs best with viscous fluids like water or oil at high speeds (up to 50,000+ RPM), where boundary layer effects are pronounced. For gases, modifications like closer spacing or multi-staging are needed to compensate for lower viscosity.

The design's simplicity—no blades means less wear from erosion or cavitation—makes it robust for harsh environments. However, challenges include managing turbulence at high speeds and optimizing for variable loads.

Jeremiah Ferwerda's Implementation of the Tesla Turbine

Jeremiah Ferwerda, an independent inventor and founder of My Tesla Power (formerly iEnergySupply), has been advancing Tesla's design since dropping out of mechanical engineering studies to focus on experimental energy technologies. His work emphasizes practical, renewable energy applications, often demonstrated at conferences like the Energy Science & Technology Conference (ESTC). By 2025, Ferwerda's prototypes have evolved into multi-stage systems capable of generating significant power, with a focus on efficiency through heat management and vacuum integration.

Key Implementations and Innovations:

- Multi-Stage Designs: Ferwerda uses two-stage setups where the first stage (centripetal flow) drives the second (centrifugal flow), creating a "fluid gearbox" effect. This involves disk surface area ratios (e.g., 3:1) to optimize viscous coupling and prevent back pressure buildup. Prototypes achieve extreme speeds: first stage up to 234,000 RPM, second up to 90,000 RPM.

- Cold Steam and Cryophorus Mode: He operates turbines in low-temperature, vacuum-enhanced modes using temperature differentials (e.g., 120°F between hot and cold tanks) to drive steam flow without pumps. This "thermodynamic transformer" extracts ambient heat, aiming for self-sustaining operation. Tests show over 42,000 RPM unloaded, with supersonic peripheral speeds.

- Power Output and Testing: Recent breakthroughs include a 6-inch prototype producing 1,300 watts in 2023, scaling to 2,200 watts in steam tests by 2024. Ferwerda incorporates Tesla's vacuum patents (e.g., British Patent 179,043) for better heat extraction, running systems "cool" to minimize losses. Materials like copper enhance condensation, and telemetry monitors RPM and pressure.

- Developments as of 2025: Ferwerda's work includes open-source kits, YouTube demonstrations (e.g., breaking the sound barrier at 95,000 RPM), and production-ready prototypes for renewable power plants. He emphasizes experimental validation over theory, targeting low-grade heat sources like solar or geothermal for electricity generation.

Ferwerda's approach symbiotic amplification—where stages boost each other via vacuum—positions his turbines as potential alternatives to inefficient engines, with ongoing refinements funded by community support.

Comparison to Conventional Turbines

Conventional turbines (e.g., impulse like Pelton or reaction like Francis/Kaplan) use bladed rotors to convert fluid energy via direct impact or pressure changes. The Tesla Turbine diverges by using friction-based boundary layers, leading to distinct advantages and drawbacks.

| Aspect | Tesla Turbine | Conventional Turbines (Bladed) |

|---|---|---|

| Design Complexity | Simple: Few moving parts (just disks and shaft), easy to manufacture and maintain. | Complex: Blades, stators, and seals increase parts count and costs. |

| Efficiency | High theoretical (up to 95%), but practical 20-60%; best at high RPM with viscous fluids. Weak friction limits low-speed/gas performance. | Often 80-90% efficient; better for gases and variable speeds, but erosion reduces longevity. |

| Durability | Excellent: No blades mean resistance to erosion, particulates, and cavitation; handles dirty/multiphase fluids. | Prone to blade damage from impurities or high speeds; requires clean fluids. |

| Speed and Power | High RPM (10,000-200,000+); good for small-scale, high-torque apps, but scaling for large power is challenging. | Lower RPM; easier to scale for megawatt outputs in power plants. |

| Cost and Applications | Low production cost; ideal for renewables, pumps, or micro-generation. Bidirectional rotation. | Higher cost; dominant in large-scale hydro, steam, or gas turbines for electricity. |

Overall, the Tesla Turbine excels in niche, low-maintenance scenarios but lags in mainstream high-power applications due to efficiency hurdles with gases. Ferwerda's implementations bridge some gaps by enhancing vacuum and staging for better gas handling.